Aerocapture for Mars Study

Decelerating interplanetary probes using Mars' atmosphere to reach a stable orbit.

Interplanetary probes are typically inserted into planetary orbit by deceleration using chemical propulsion, which requires a substantial amount of propellant, making up a significant portion of the vehicle mass. An alternative to this method is Aerocapture, which uses atmospheric drag to slow down the spacecraft, reducing the need for heavy propellant. This is not to be confused with Aerobraking, where atmospheric drag is used after orbit insertion to fine-tune the orbit, which has been successfully used in the past.

This study, conducted by Vorticity, funded by the European Space Agency (ESA), explored the feasibility of aerocapture for Mars missions, specifically through a concept demonstration aimed at increasing the Technology Readiness Level (TRL) and heritage of this technique for future missions.

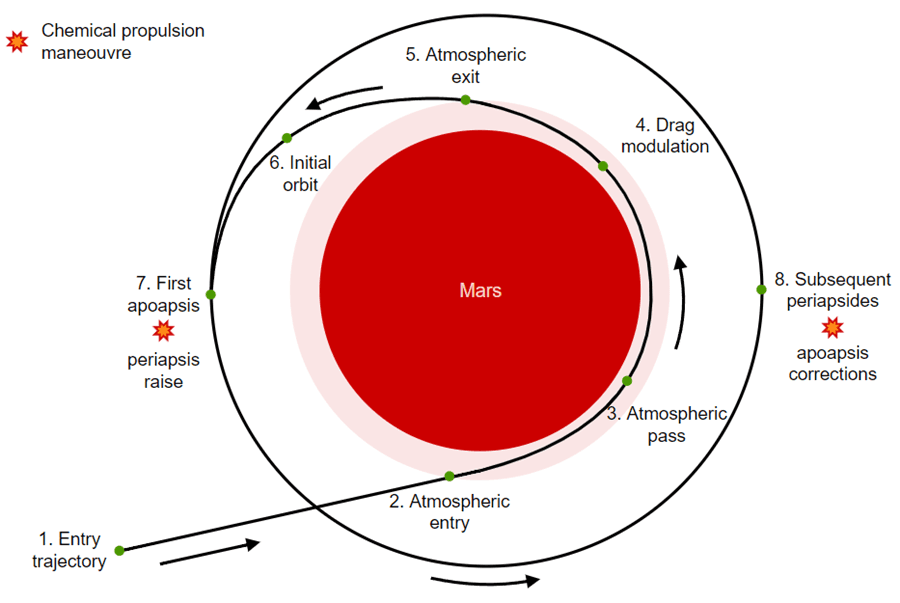

Mars aerocapture concept of operation

Two mission options were considered:

Piggy-back Mission (90 kg at Mars arrival): A rapid demonstration mission to test basic aerocapture technology.

Standalone Mission (400 kg at Mars arrival): A more advanced mission that would serve as a stepping stone toward larger, more complex missions.

In the proposed aerocapture concept, the spacecraft uses an inflatable decelerator that is deployed as it enters the Martian atmosphere. The decelerator generates drag, slowing the spacecraft down. Midway through the atmospheric pass, the decelerator is jettisoned or retracted, increasing the spacecraft’s ballistic coefficient and giving it control over its final orbital apoapsis. After exiting the atmosphere, the spacecraft performs a periapsis raise manoeuvre to prevent a second atmospheric pass, then establishes communication with Earth and manoeuvres into its target orbit.

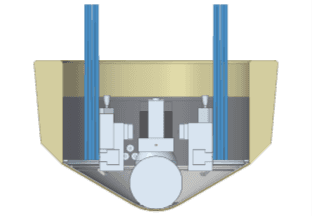

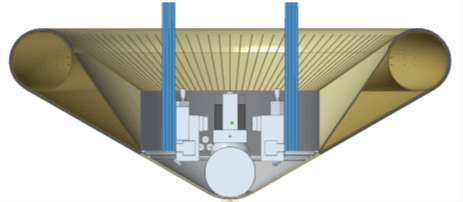

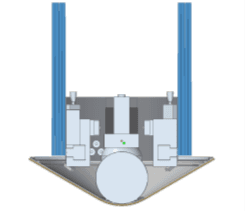

Standalone vehicle sequence of events. Inflatable decelerator stowed; decelerator deployed; decelerator released.

Achieving a precise orbital insertion is challenging due to uncertainties in entry parameters, atmospheric conditions, and vehicle properties. These variabilities make it impossible to achieve the target apoapsis with a fixed ballistic coefficient. The spacecraft’s Guidance, Navigation, and Control (GNC) system must therefore be able to autonomously modulate lift and / or drag during entry to compensate for these uncertainties.

The chosen method involves a single event during atmospheric entry where the spacecraft switches from a low to a high ballistic coefficient by jettisoning or retracting the decelerator. The ratio between the final and initial ballistic coefficients determines the spacecraft’s control authority over its trajectory. A higher ratio requires a larger decelerator, which increases the mass of the vehicle.

For aerocapture to be viable, it must result in a higher payload mass in orbit for a given arrival mass than traditional chemical propulsion. A critical factor in the design process is minimizing uncertainties in entry parameters, atmospheric conditions, and vehicle characteristics to reduce the need for large decelerators. The atmospheric model used in the design process plays a pivotal role in determining the size of the decelerator. Accurate atmospheric modelling and a full understanding of model uncertainties are essential for successful aerocapture missions.

This study concluded that if uncertainties in atmospheric conditions and vehicle properties can be sufficiently reduced, the relatively simple technique of single-event drag modulation aerocapture could deliver larger payload masses into Mars orbit than conventional chemical propulsion methods. This would make aerocapture a promising alternative for future Mars missions, potentially reducing the mass required for interplanetary probes.